Espelho

Mirror

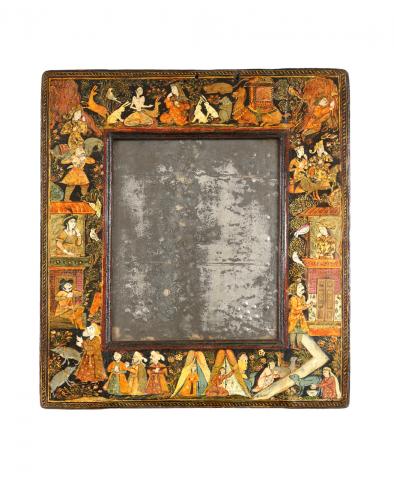

Amalgam mirror and polychrome painting in shellac on wood

Europe (mirror), and Iran, Isfahan (frame), ca. 1610-1630

Dim. 39,0 x 34,2 x 2,5 cm

Espelho

Irão, Isfahan (moldura); Europa (espelho), e ca. 1610-1630

Madeira, pigmentos, goma-laca e amálgama de estanho (espelho)

Dim. 39,0 x 34,2 x 2,5 cm

23,5 X 18,5 cm (espelho)

7,8 cm (perfil da moldura)

This unique amalgam mirror, with its ‘lacquered’ wooden frame, bridges Iran and Europe, East and West, in different and meaningful ways. The mirror is European, featuring a surface with wheel-engraved decoration: a border with interspersed dots and dotted rosettes in the corners.

The manufacture of glass mirrors was a well-kept secret throughout the first centuries of the early modern period. By the 1560s, Venetian glassmakers, who had successfully produced large sheets of broad glass using almost colourless glass known as cristallo, devised a new technique of applying tin foil to the back using mercury. The technique of using a tin-mercury amalgam was the primary method for producing glass mirrors from the sixteenth to the early twentieth century, with the Venetian monopoly over its production lasting until the end of the seventeenth century. Consequently, the ownership of mirrors produced through this time-consuming, delicate, and perilous technique was largely restricted to the affluent elite. Crafted around six decades after the first Venetian examples, the present mirror was either produced in Venice (on the island of Murano) or, judging from its wheel-engraved decoration, in the Netherlands. A Netherlandish amalgam mirror in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (inv. 4471-1857), decorated with identical wheel-cut motifs, dates to about 1620. Framed inside a highly elaborate carved frame of architectural design, its glass mirror (27.6 x 23.8 cm) features a wheel-engraved linear border with interspersed dots running along the edges and large dotted rosettes set on the corners.

Adding to an already extraordinary and rare example of an early European glass mirror, further embellished with wheel-engraved decoration, the frame that has since protected it is a unique example of Safavid art from the reign of Shah ‘Abbas I (r. 1588-1629). Probably modelled after earlier and contemporary European examples, the mirror is encased in an almost square, flat, and broad frame. The wooden frame is masterfully painted with figurative scenes over a black ground in vivid colours, using a mixture of shellac and pigments highlighted in gold. The painted decoration was directly applied to the wood and, in certain intricate details such as the characters' faces, layered over a raised surface covered with paper. A narrow rope-like border in gold decorates its edges, while the frame thickness features a frieze of vegetal sprays on a white ground. The carved underside of the frame, with its recessed mouldings, is painted with floral scrolls highlighted in gold over a black ground. A plain backboard covers the later wooden stretchers of the back, where an old, probably nineteenth-century sticker bears the inscription 'n.º 82 Perse,' suggesting its probable association with a French collection.

The brightly painted figurative decoration consists of individual scenes running along the flat moulding of the frame, with some depicting well-known episodes from the much-appreciated classic of Iranian literature, Nizami’s Khamsa. Nizami Ganjavi (1141-1209) is considered the greatest romantic epic poet in Persian literature. Born in Ganja, in present-day Azerbaijan, during the Seljuk dynasty, Nizami spent his life in the South Caucasus. Highly influential in early Safavid art, Nizami’s main poetical work is the set of five long narrative poems known as Khamsa or ‘Quintet’. The second story tells the tragic love story of ‘Khusrau and Shirin’ between the Sasanian king Khusrau II and the Armenian princess Shirin, who becomes queen of Persia. The third story of the Khamsa is known as ‘Layla and Majnun’, akin to the tale of Romeo and Juliet, where the protagonists are unable to unite due to a family feud.

The scenes painted on the frame are arranged into eight groups: two landscape scenes on the top and bottom sections; and three vertically stacked scenes on either side of the mirror. The top section depicts an encounter between the bare-chested ascetic Majnun and Layla. In the wilderness, a host of hares, deer, a crouching lion, a sitting wolf, birds perched on trees, and a crouched camel fitted with a palanquin or litter for carrying Layla all seem to have stopped to witness their love story. On the top left corner, a scene from Nizami’s ‘Khusrau and Shirin’ portrays the sculptor Farhad carrying on his shoulders the Armenian princess Shirin on horseback. Farhad had fallen in love with Shirin, becoming Khusrau’s love rival. On the top right corner, the scene depicts a male and female on horseback, while a man over them picks his axe into the rocks. This represents Farhad, who Khusrau had sent into exile to the Behistun Mountain, burdened with the impossible task of carving stairs out of the cliff rocks.

The middle sections flanking the mirror feature, on either side, a two-storey building. On the left, a male figure in European attire, with his hands clutched together resting on a cane, sits cross-legged on the lower register next to a closed door. Above him, an upright female figure, similarly dressed, gazes into the horizon from a balcony next to a pair of singing birds perched on a tree. On the right, almost as a mirrored image, an identical two-storey building, with a man in Persian courtly attire seems to engage in conversation with a princess on her balcony. This scene may depict the much-anticipated encounter between Khusrau and Shirin when the king goes to her palace to see her, only to be reproached for being drunk and not allowed inside the castle. Finally, the lower section depicts what seem to be two scenes. On the left, next to two wild boars, a tall male figure in local attire and white beard - perhaps a Sufi saint - is followed by three dervishes (Sufi mendicants), with the last one carrying the typical large wooden boat-shaped beggar’s bowl to collect money and other goods - a kashkul. On the right, a group of women in courtly attire and their female servants have set tents near an elbow-shaped channel; on the lower right, a maid milks a goat. This channel may be associated with the milk channel that Farhad cut out from the mountain, flowing into a pool at the foot of Shirin’s palace.

Not surprisingly, the painting style employed in the current frame follows that of contemporary Safavid manuscript painting and the more decorative character of some rare surviving ‘lacquer’ book bindings, which exhibit the same stylistic features. A comparable style can be found in a manuscript of Khusrau and Shirin featuring paintings by Reza ‘Abbasi (d. 1635) in the Victoria and Albert Museum (inv. MSL/1885/364). Though earlier, dated to 1559-1560, one fine example of such ‘lacquer’ bindings, similarly decorated with brightly painted figures on a black ground, belongs to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris (Ms. or., Persan 245). The front cover of this binding depicts a well-known episode of Nizami’s Khamsa when Khusrau first catches sight of Shirin bathing in a stream. Similarly painted with brightly coloured shellac, a book stand or rahla (58.0 x 20.0 cm) in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg (inv. VP-184), from the first half of the seventeenth century, depicts courtly figures having meals in luxuriant gardens over a black ground. The shared style borrowed from contemporary book paintings, along with identical methods of depicting figures, trees, and flowers highlighted in gold, makes it an ideal comparative object to the present mirror frame.

It is curious to note that the figures of Khusrau and Shirin on the right of our frame are mirrored by the loving pair on the left, dressed in European, likely Portuguese attire. He wears a short-sleeved skirted jerkin (roupeta) over his doublet (gibão), hoses (calças), knee-high riding boots, and a wide-brimmed hat. With a more elaborate back hat decorated with a feather, she wears a similar skirted jerkin over her skirt. Two male figures, similarly attired in European clothing and sporting identical black hats, are depicted on a tile-work panel from around 1600-1610. Originally placed in a now-lost royal garden pavilion in Isfahan from the time of Shah ‘Abbas, this panel is part of the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (inv. 03.9a). It is worth emphasising that later Safavid depictions of Portuguese or Europeans, from the 1640s and 1650s, become increasingly less accurate and more stylised, combining foreigner attire with local garments. In the early sixteenth century, Portugal, a major maritime power, sought to establish trade routes and access the lucrative markets in the East at a time when the Safavids, under Shah Isma’il I (r. 1501-1524) and later, Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524-1576) and Shah ‘Abbas, emerged as a dominant force in Iran. Portuguese presence in Hormuz and rule over its domains on both sides of the Gulf secured control over the local trade in silk textiles, carpets, horses, and pearls. Despite occasional conflicts, periods of diplomatic engagement between the two powers saw exchanged missions and agreements to facilitate trade and navigation. Gifts sent from Portugal or Portuguese-ruled India and other Asian territories supplied a myriad of exotic artworks and unfamiliar objects that were met with great enthusiasm at the Safavid court.

The creation of this 'lacquered' mirror frame should be viewed in the context of increasing Western influence and a growing fascination with European commodities and aesthetics within the Iranian court. Made in the later years of Shah ‘Abbas’s reign, this rare object mirrors the cosmopolitanism of Safavid society. It was likely made in the court workshops in Isfahan, the new capital of Safavid Iran since 1598. This mirror frame’s creation may be linked to the presence of Armenian merchants, established by the 1606 edict of Shah ‘Abbas in New Julfa, the Armenian district of Isfahan. Armenians were among the most westernised individuals at the Safavid court, commissioning portraits from European painters and collecting foreign artworks, such as European clocks, glass, and silver plate. In a way, they are ‘depicted’ in the mirror frame’s decoration by the portrayal of the Armenian (and Christian) princess Shirin. The lasting appreciation for glass mirrors would transform into a craze in later periods, evident in the ubiquitous mirror-tile mosaic decoration in Iranian secular and religious architecture. An iconic example is the nineteenth-century Mirror Hall of the Golestan Palace in Tehran. While similarly decorated mirror frames with coloured shellac are known, primarily designed as closed boxes or cases, they mostly date to the early eighteenth century in the late Safavid period. The present mirror frame, a unique testimony of the presence of European amalgam mirrors in early seventeenth-century Isfahan, stands as a powerful example of cultural and artistic exchange between Europe and Safavid Iran.

Hugo Miguel Crespo

Centre for History, University of Lisbon

--

Este singular espelho de amálgama de estanho com sua moldura de madeira acharoada, liga o Irão à Europa, o Oriente ao Ocidente, de formas diferentes e com grande significado.

O espelho é europeu, apresentando decoração lapidada à roda: semi-esferas, desenhando uma cercadura periférica e rosetas nos cantos. O fabrico de espelhos de vidro permaneceu um segredo bem guardado ao longo dos primeiros séculos da Época Moderna. Na década de 1560, os vidreiros venezianos, que haviam produzido com sucesso grandes folhas de vidro quase incolor conhecido como cristallo, desenvolveram uma nova técnica de aplicação de folha de estanho no verso usando mercúrio. A técnica da amálgama de estanho e mercúrio foi o principal método de produção de espelhos de vidro do século XVI até aos inícios do século XX, tendo o monopólio veneziano de sua produção perdurado até ao final do século XVII. Este facto explica como o consumo de espelhos de vidro, produzidos através deste processo lento, delicado e perigoso, estava limitado às famílias mais abastadas.

Datando de cinco décadas após o início da produção dos primeiros exemplares venezianos, este espelho terá sido produzido em Veneza, na ilha de Murano ou, a julgar pela sua decoração lapidada à roda, nos Países Baixos. Um espelho neerlandês de amálgama de estanho no Victoria and Albert Museum, Londres (inv. 4471-1857), decorado com motivos idênticos lapidados à roda, data de cerca de 1620. Protegido numa complexa moldura entalhada de feição arquitectónica, (27,6 x 23,8 cm) apresenta cercadura semelhante, linear e ponteada de “semi-esferas” periférica e as mesmas rosetas nos cantos.

A um, já de si extraordinário e raro, espelho seiscentista europeu com decoração lapidada à roda, acresce a moldura - desde então o protege - exemplar único da arte safávida do reinado de Xá ‘Abbas I (r. 1588-1629). Provavelmente replicando modelos europeus coevos ou pouco anteriores, o espelho é protegido por moldura rectangular, larga e plana na frente. Com estrutura em madeira, é magistralmente pintada com cenas figurativas em cores vivas, sobre fundo negro, utilizando uma mistura de goma-laca e pigmentos, avivadas a ouro. A pintura foi aplicada directamente sobre a madeira e em alguns casos - como os rostos dos personagens - sobre uma superfície elevada com papel.

Uma cercadura estreita encordoada a ouro decora as arestas, enquanto a espessura da moldura apresenta friso de enrolamentos vegetalistas sobre fundo branco.

O tardoz, entalhado com modenaturas e friso de arcarias, é decorado com enrolamentos florais avivados a ouro, sobre fundo negro. Um painel liso cobre uma estrutura de reforço em madeira, onde numa antiga etiqueta, provavelmente do século XIX, lemos - “n.º 82 Perse” -, sugerindo ter feito parte de uma provável colecção francesa.

A decoração figurativa, em cores vivas, consiste em cenas individuais dispostas ao longo da moldura, algumas retratando episódios bem conhecidos do clássico da literatura iraniana, o Khamsa de Nizami. Considerado o maior poeta épico romântico da literatura persa, Nizami Ganjavi (1141-1209) nasceu em Ganja, no actual Azerbaijão, durante a dinastia seljúcida, e tendo vivido sempre na Transcaucásia. De grande influência logo nos inícios da arte safávida, a principal obra poética é o conjunto de cinco longos poemas narrativos conhecidos como Khamsa ou “Quinteto”. O segundo poema conta a trágica história de amor intitulada “Khusrau e Shirin”, entre o rei sassânida Khusrau II e a princesa arménia Shirin, que se tornaria rainha da Pérsia. O terceiro poema do Khamsa, conhecido por “Layla e Majnun”, que, à semelhança de Romeu e Julieta, não podiam ver-se devido à rivalidade das suas famílias. Os quadros dispõem-se em oito cenas de paisagem não tendo sido possível identificar um dos temas retratados.

Na tábua superior está representado o encontro entre o asceta Majnun, de peito descoberto, e Layla. Num bosque, uma multidão de animais - lebres, veados, um leão agachado, um lobo sentado, pássaros empoleirados nas árvores e um camelo sentado com o palanquim ou liteira para carregar Layla - parecem ter parado para testemunhar a história de amor.

No canto superior esquerdo, um cenário de “Khusrau e Shirin” retrata o escultor Farhad carregando nos ombros a princesa arménia Shirin a cavalo. Farhad apaixonara-se por Shirin, tornando-se no rival amoroso de Khusrau. No direito, um casal a cavalo e por cima, um homem que crava o seu machado nas pedras. Trata-se, mais uma vez, de Farhad, que Khusrau enviara para o exílio na montanha de Behistun com a impossível tarefa de entalhar escadas na encosta rochosa.

Em ambas as tábuas laterais, existe um edifício de dois andares. À esquerda, uma figura masculina em traje europeu, com as duas mãos apoiadas numa bengala, senta-se de pernas cruzadas junto a uma porta fechada. No andar superior, uma figura feminina em pé - numa varanda e também com indumentária europeia - fita o horizonte, junto a um par de pássaros canoros empoleirados numa árvore. À direita, como que em espelho e num edifício idêntico, um homem em traje de corte persa, parece conversar com uma princesa que está à varanda. Trata-se muito provavelmente do tão esperado encontro entre Khusrau e Shirin, quando o rei se desloca ao seu palácio para a visitar e a sua entrada sido recusada pela princesa, que repreendeu o rei, por se encontrar alcoolizado.

Por fim, no elemento inferior, parecem estar descritas duas cenas. À esquerda, junto a dois javalis, um homem alto em traje local e barba branca - talvez um santo sufi - é acompanhado por três dervixes (pedintes sufis), o último segurando um kashkul - a típica e grande tigela de esmolas em forma de barco, para receber dinheiro e outros bens. À direita, duas mulheres em traje de corte - dentro de tendas - e suas criadas, perto de um canal em forma de cotovelo; no canto inferior direito, uma das serviçais ordenha uma cabra. Este canal pode ser identificado com o “canal de leite” que Farhad entalhou na montanha, desaguando num tanque, junto ao palácio de Shirin.

Sem surpresa, o estilo pictural desta moldura assemelha-se à coeva pintura de manuscritos do período safávida filiando-se, o seu carácter mais decorativo, nalgumas raras encadernações “lacadas” que chegaram até aos nossos dias e que partilham as mesmas características estilísticas. Estilo afim encontramos num manuscrito de Khusrau e Shirin com pinturas de Reza ‘Abbasi (m. 1635) no Victoria and Albert Museum (inv. MSL/1885/364). Embora anterior, datado de 1559-1560, um belo exemplo destas encadernações de “laca”, decoradas com figuras pintadas a cores vivas sobre fundo negro, pertence à Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris (Ms. ou., Persan 245). Na pasta superior desta encadernação vemos o episódio bem conhecido do Khamsa de Nizami, em que Khusrau vê pela primeira vez Shirin, a tomar banho num ribeiro. Igualmente pintada a goma-laca de cores vivas, uma estante para livros ou rahla (58,0 x 20,0 cm) do State Hermitage Museum, São Petersburgo (inv. VP-184), da primeira metade do século XVII, representa figuras de corte a merendar em viçosos jardins sobre fundo negro. O mesmo estilo das pinturas de livros coevos e idêntica forma de representar figuras, árvores e flores, sempre realçadas a ouro, fazem desta estante um objecto perfeito de comparação com a nossa moldura.

É curioso notar como as figuras de Khusrau e Shirin à direita, são espelhadas pelo casal apaixonado na tábua esquerda, vestido com trajes europeus, provavelmente portugueses. Ele veste roupeta de mangas curtas sobre o gibão, calças, botas de montar até o joelho e chapéu de aba larga. Com semelhante chapéu, mas decorado com uma pena, ela veste idêntica roupeta de abas largas, sobre a saia. Duas figuras masculinas, também vestidas à europeia com chapéus pretos idênticos, são retratadas num painel de azulejos de cerca de 1600-1610 - originalmente colocado num régio pavilhão de jardim em Isfahan, hoje perdido - do reinado de Xá ‘Abbas, na colecção do Metropolitan Museum of Art, Nova Iorque (inv. 03.9a). De sublinhar que as ulteriores representações safávidas de portugueses ou europeus, das décadas de 1640 e 1650, tornar-se-ão cada vez menos precisas e mais estilizadas, combinando os trajes estrangeiros com indumentária local. No início do século XVI, Portugal, uma grande potência marítima, procurou estabelecer rotas comerciais e aceder aos lucrativos mercados do Oriente, numa altura em que os safávidas, sob a égide do Xá Isma‘il I (r. 1501-1524) e, mais tarde, do Xá Tahmasp (r. 1524-1576) e de Xá ‘Abbas, emergiam como força dominante no Irão. A presença portuguesa em Ormuz e a administração dos seus domínios de ambos os lados do Golfo garantiriam o controle do comércio local de têxteis de seda, tapetes, cavalos e pérolas. Apesar dos ocasionais conflitos, períodos de aproximação diplomática entre as duas potências estimularam a troca de embaixadas e acordos com vista a facilitar o comércio e a navegação. As ofertas - enviadas desde Portugal ou da Índia sob domínio luso e de outros territórios asiáticos -proveram uma miríade de obras de arte exóticas e objectos invulgares recebidos com grande entusiasmo na corte safávida.

A produção desta moldura de espelho acharoada deve ser entendida dentro deste contexto de influência ocidental e do interesse crescente pelas mercadorias e pela estética europeia na corte iraniana. Dos últimos anos do reinado de Xá ‘Abbas, este raro objecto reflecte o cosmopolitismo da sociedade safávida. Terá sido provavelmente produzido nas oficinas de corte em Isfahan, a nova capital do Irão safávida desde 1598.

A génese desta moldura de espelho pode estar ligada à presença de mercadores arménios, estabelecidos por decreto de Xá ‘Abbas de 1606 em Nova Julfa, o bairro arménio de Isfahan. Os arménios contavam-se entre os indivíduos mais ocidentalizados na corte safávida, encomendando retratos de pintores europeus e coleccionando obras de arte estrangeiras, como relógios, vidros e prataria de aparato europeus. De certa forma, eles surgem “retratados” nesta moldura, através do retrato da princesa arménia (e cristã) Shirin. O gosto imorredouro por espelhos de vidro transformar-se-ia numa completa mania em períodos posteriores, evidente na onipresente decoração em mosaico de espelho na arquitectura secular e religiosa iraniana. Um exemplo icónico é o Salão dos Espelhos do Palácio do Golestão, do século XIX, em Tehran.

Embora se conheçam molduras de espelho também decoradas a goma-laca de cores, usualmente na forma de caixas ou estojos fechados, estas datam sempre dos inícios do século XVIII, já no final do período safávida, pelo que esta obra de arte, testemunho único da presença de espelhos europeus de amálgama de estanho em Isfahan no dealbar de Seiscentos, constitui um testemunho eloquente do intercâmbio cultural e artístico entre a Europa e o Irão safávida.

Hugo Miguel Crespo

Centro de História, Universidade de Lisboa

Bibliografia:

Sheila R. Canby, Shah ‘Abbas. The Remaking of Iran (cat.), Londres, The British Museum Press, 2009

Moya Carey, Persian Art. Collecting the Arts of Iran for the V&A, Lodres, V&A Publishing, 2017

Moya Carey, Meeting in Isfahan. Vision and Exchange in Safavid Iran (cat.), Dublin, Chester Beatty Library, 2022

Miguel Castelo-Branco (ed.), Portugal no Golfo Pérsico. 500 Anos, Lisboa, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, 2018

Dejanirah Couto, Rui Manuel Loureiro (eds.), Revisiting Hormuz. Portuguese Interactions in the Persian Gulf Region in the Early Modern Period, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2008

Farshid Emami, “All the City’s Courtesans: A Now-Lost Safavid Pavilion and Its Figural Tile Panels”, Metropolitan Museum Journal 54 (2019), pp. 62-86

Per Hadsund, “The Tin-Mercury Mirrors: Its Manufacturing Techniques and Deterioration Processes”, Studies in Conservation 38.1 (1993), pp. 3-16

Carla Alferes Pinto, “Presentes ibéricos e «goeses» para ‘Abbas I: a produção e consumo de arte e os presentes oferecidos ao Xá da Pérsia por D. García de Silva y Figueroa e D. frei Aleixo de Meneses”, in Rui M. Loureiro, Vasco Fernandes (eds.), Estudos sobre Don García de Silva y Figueroa e os «Comentários» da embaixada à Pérsia (1614-1624), vol. 4, Lisboa, Centro de História de Além-Mar, 2011, pp. 245-278

Carla Alferes Pinto, “The Diplomatic Agency of Art between Goa and Persia: Archbishop Friar Aleixo de Meseses and Shah ‘Abbās I in the Early Seventeenth Century”, in Zoltán Biedermann, Anne Gerritsen, Giorgio Riello (eds.), Global Gifts. The Material Culture of Diplomacy in Early Modern Eurasia, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 150-170

Jennifer M. Scarce, “The Architecture and Decoration of the Gulistan Palace: The Aims and Achievements of Fath ‘Ali Shah (1797-1834) and Nasir al-Din Shah (1848-1896)”, Iranian Studies 34.1-4 (2001), pp. 103-116.

Sara J. Schechner, “Between Knowing and Doing: Mirrors and Their Imperfections in the Renaissance”, Early Science and Medicine 10.2 (2005), pp. 137-162

Nuno Vassallo e Silva, “Diplomatic embassies and precious objects in Hormuz: an artistic perspective”, in Dejanirah Couto, Rui Manuel Loureiro (eds.), Revisiting Hormuz. Portuguese Interactions in the Persian Gulf Region in the Early Modern Period, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2008, pp. 217-225

Tim Stanley, “The Rise of the Lacquer Binding”, in Jon Thompson, Sheila R. Canby (eds.), The Hunt for Paradise. Court Arts of Safavid Iran, 1501-1576 (cat.), Milão, Skira, 2003, pp. 184-200

Ghoncheh Tazmini, “The Persian-Portuguese Encounter in Hormuz: Orientalism Reconsidered”, Iranian Studies 50.2 (2017), pp. 271-292

- Arte Colonial e Oriental

- Artes Decorativas

- Diversos