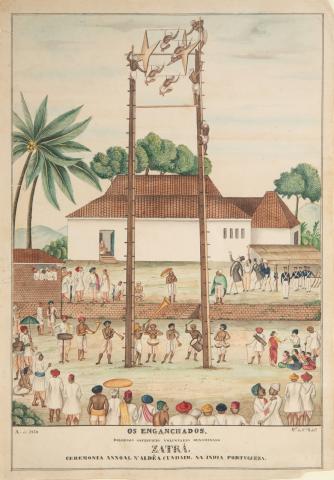

Os Enganchados, 1850

Manuel da Cunha Maldonado

“Os Enganchados”, 1850

Watercolour and Indian ink on paper

Dim.: 39.0 x 27.0 cm

Inscribed: «Os Enganchados, doloroso sacrifício voluntario denominado Zatrá. Ceremonia annoal n’aldêa cundaim, na india portuguesa».

Provenance: Spanish collection

Mel da Cª Maldonado

Os Enganchados, 1850

Aguarela e tinta-da-china s/ papel

Dim.: 39,0 x 27,0 cm

Legenda: «Os Enganchados, doloroso sacrifício voluntario denominado Zatrá. Ceremonia annoal n’aldêa cundaim, na india portuguesa».

Proveniencia: coleção espanhola

A water-coloured Indian ink painting on paper depicting the penance ceremony known as “Os Enganchados” (The Hooked), the Hindu celebration of the Zatra ritual at the village of Cundaim, in the Goan province of Ponda. As stated in the caption, this annual practice would be a four people “painful voluntary sacrifice”, with the purpose of appeasing the Gods and earning prosperity for the village and its inhabitants.

Signed lower right by its author, Manuel da Cunha Maldonado, a cartograph and artillery sergeant , it was painted in 1850, as referred in the opposite left corner.

The description of Os Eganchados, published in O Encyclopedico, Jornal d’Instrucção e Recreio in 1842, describes the same ceremony, occurred on December 11th, 1841, at Cundaim. As per tradition, the celebrations started with the gathering of hundreds of villagers around a group of musicians playing metal made, wind and percussion indigenous instruments such as “Arab, Dôll, Sômor, Chinga, Cornon, and others”, around the central ceremonial structure. Two mango wood (Mangifera indica) poles, 9 metres tall (twenty cubits), raised vertically at 2,25 metres (five cubits) from each other and fitted with bamboo culms at every 0,45 metres (one cubit), to be used as steps to the top. The poles were joined by betel palm trunks (Areca catechu): the upper as the axis for two four-pointed star shaped structures, each connected to the other star tips by wooden rods and, below, a broad board that enabled the participants movement.

To the right background, separated from the main scene by a terrace, a stationed infantry battalion for controlling the crowds and, behind it, a wood-built temple surrounded by small single floored structures, destined to accommodate the villagers that had travelled from afar. All the participating volunteers were Shudra, the fourth lower of the five Hindu castes (varnas), comprising of farmers, artisans and labourers. As a reward for their sacrifice, they, and their families, were entitled to rather “mediocre” lots of farmland.

Before the ceremony, the four participants had their beards and nails trimmed and followed a purifying ritual in which they responded to prayers by an elder, the protocol leader. This ritual took place in a tank and while water was thrown over their hands, their feet were therein immersed. Following from this practice, they were handed a rumal, a thick white cloth to be tied as a headscarf, and a puruem, a piece of fabric to be wrapped around the waist and the hips, and crowned with flower garlands, one detail that is omitted from our depiction. A lacquered rod, simulating a sword, was presented to each one of them to be held in the right hand. In addition, they were also given a linen rope, of four hand straps joined by a single knot at the top, to fasten to the irons and, consequently, the central knot to the rotating wooden structure. Lastly, while smoking a concoction of opium and cannabis, they danced around the sacrificial structure and the lodgings, before entering the temple.

At sunrise the following day, preceded by the crowd and by the musicians playing their instruments, the volunteers abandoned the temple, linen rope around their necks, hooks in the left hand and lacquered rod in the right. Approximately 328 metres, or 120 steps, away from the sacrificial spot, the ritual in which the four were pierced on their backs by the blacksmith with a bezel iron and the hooks fitted, took place.

From there they were guided to the structure, which they climbed with some helpers of their own caste, up to the board beneath the two stars. Once at the top their knees were bent and tied, so that the feet did not touch the structure, their body length being therefore shortened. During this initial process they were suspended by the left arm while their assistants tied the linen rope to the frame rotating axis. On releasing the left arm, and only suspended by the hooks, they waved at the audience while moving the rod with the right arm, a detail that is not illustrated in the present depiction. Assisted by those on the platform, they slowly rotated three times, thus ending the sacrifice. They would finally climb down in pairs to be greeted and cherished on touching the ground. Back in the temple, they laid down in prone position to get the hooks removed .

It is well documented that identical rituals were also staged during the Zatra in the villages of Bally and Sirigao, in the Province of Bicholim . Both The Times of India, through the Dacca News, and the Hurkaru, a Kolkata newspaper, refer other ceremonies during which these practices took place; the Konkan Jatra and the Charak Puja .

In 1844, José Ferreira Pestana, the territory Governor, determined the prohibition of such ceremonies in Goa (Government Bulletin no. 50/1844). His official degree stated that:

“Whereas no civilized nation may allow that atrocities such as hanging persons from hooks and piercing the flesh be committed for all to see (…) I ordered the clerk of the Cundaim village of Ponda be called before me and I made known to him the disapproval of the government of His Most Faithful Majesty (…)”.

This interdiction was celebrated in various publications, namely in the 1865 Archivo de Pharmacia, in these terms:

“We hope that soon other equally repulsive religious Hindu habits and practices, will be similarly suppressed” .

During Ferreira Pestana second tenure however, on February 9th, 1866, the Goan Betki villagers requested, through Minguel da Costa, the reinstatement of this ceremony as, according to their petition, upon the Hooked ritual prohibition, various epidemics and misfortunes had affected their village . According to this report, the government had solely forbidden the ceremony in Cundaim, the prohibition in other villages being imposed by the local authorities .

“This prohibition, far from being advantageous and beneficial to the Community and to the other inhabitants of the village, has been the source of all sorts of evils and successive misfortunes for the inhabitants of the village, which has been seriously afflicted by epidemics, an increase in mortality, a drastic drop in agricultural production, resulting in great and irreparable suffering, (…) all sorts of calamities, as a result of water drying up in the lakes (…). According to old beliefs, the village people are convinced that all these evils can be attributed to the failure to perform the Ceremony of the Hooked Ones (…)”.

The request is reinforced “in view of such practices existing in the rest of India”.

On February 9th, 1866, the Governor replied rejecting the petition, and issuing the following order:

“When the interpreter of the wishes of the petitioners, Minguel da Costa, who wrote this petition, is able to convince me that the petitioners have been suffering from the evils afflicting them because of being deprived of the Zatra of the Hooked Ones in Betki, consideration may be given to this request.” (1866, p.50 – Archivo de Pharmacia) .

Apparently, Minguel da Costa did not reply to the Governor and, as such, the ceremony has been forbidden to the present day.

Marta Silva Pereira

--

Pintura a aguarela e tinta-da-china sobre papel representando cerimónia de penitência Os Enganchados, celebração integrada no ritual Zatrá do templo hindu de Cundaim, aldeia pertencente à Província de Pondá, em Goa. Como indicado na legenda, esta prática anual seria um «doloroso sacrifício voluntário» de quatro indivíduos, com o objetivo de apaziguar os deuses e granjear prosperidade para a aldeia e os seus habitantes.

Assinado no canto inferior direito, podemos inferir que o autor foi Mel. da Ca. Maldo, pintor até à data não identificado, e que terá sido pintada no ano de 1850, com indicado no canto inferior esquerdo.

A descrição de Os Eganchados publicada em O Encyclopedico, Jornal d’Instrucção e Recreio em 1842 relata a mesma cerimónia, ocorrida a 11 de dezembro de 1841, em Cundaim.

As celebrações iniciam-se com o ajuntamento de centenas de aldeões em redor de diversos músicos, que tocam instrumentos metálicos de sopro e percussão. De acordo com o anterior relato, seriam «Arab, Dôll, Sômor, Chinga, Cornon e outros instrumentos gentílicos», em torno da estrutura central da cerimónia. Dois postes de madeira de mangueira (Mangifera indica) com nove metros de altura (vinte côvados), são erguidos à distância de dois metros e vinte e cinco centímetros (cinco côvados), ambos atravessados por colmos de bambu, com um intervalo de quarenta e cinco centímetros (1 côvado), que irão servir de degraus, para permitir a subida ao topo. Os pilares estão unidos por troncos de arequeira (Areca catechu): o superior, serve de eixo a duas estruturas em forma de estrela, com quatro pontas ligadas às extremidades da outra estrela por varas de madeira e, por baixo, uma tábua larga que irá permitir a movimentação dos figurantes.

Separado por um socalco, em segundo plano e à direita, observamos um batalhão de infantaria, que teria como propósito o controlo das multidões e, mais ao fundo, um templo em madeira, rodeado de pequenas edificações térreas, para albergar os aldeões que se deslocam para este festejo.

Todos os voluntários da cerimónia pertencem à casta Sudra. Os Sudras ou Shudras são a quarta mais baixa, das cinco castas (varṇa) hindus, constituída por camponeses, artesãos e operários. Como recompensa pelo seu sacrifício, os ventureiros e as suas famílias terão direito a «medíocres » porções de terreno de cultivo.

Antes da cerimónia, é cortada a barba e as unhas aos quatro voluntários, seguindo-se um ritual de purificação, onde respondem a orações de um ancião, líder da cerimónia de Os Enganchados. Este ritual realiza-se num tanque onde é lançada água sobre as mãos dos indivíduos, que têm os pés nela mergulhados.

Após a o ritual de purificação, recebem um Rumal (lenço branco de tecido espesso a ser colocado na cabeça) e um Puruem (pano enrolado à cintura, circundando os quadris), e são coroados com grinaldas de flores (facto curiosamente não evidenciado nesta representação). Uma vara lacrada, imitando uma espada, é oferecida a cada um, que a coloca na mão direita. Também uma corda de linho, com quatro alças unidas por um só nó no topo, lhes é dada para prender aos ferros e, por conseguinte, o nó central à estrutura rotativa de madeira. É- lhes ainda ofertado um preparado de ópio e canábis que fumam, enquanto dançam em redor da construção sacrificial e das edificações, antes de entrar no templo.

Ao nascer do sol, precedidos da multidão e dos músicos que tocam os seus instrumentos, os voluntários abandonam o templo, com a corda de linho ao pescoço, os ganchos na mão esquerda e empunhado vara lacrada, na direita.

Ligeiramente afastados do local do sacrifício (cerca de trezentos e vinte e oito metros, ou cento e vinte passos) inicia-se a cerimónia de perfuração, em que os quatro são trespassados pelos ganchos. O ferreiro faria furos nas costas com um ferro de bisel, introduzindo o gancho pelo lado oposto.

Daqui são encaminhados para o local, que trepam, com alguns ajudantes da mesma casta, colocando-se na tábua por baixo das estrelas. Os joelhos são dobrados e atados, para que os pés não toquem em nenhuma parte da estrutura, tendo o corpo obrigatoriamente de ficar encolhido. Durante este processo inicial, são suspensos pelo braço esquerdo e os companheiros unem a corda de linho ao eixo rotativo da estrutura.

Ao largar o braço esquerdo, suspensos somente pelos ganchos, acenam à população, enquanto movimentam a vara com o braço direito (movimento não ilustrado nesta representação). Ajudados pelas pessoas que se encontram na plataforma, dão lentamente três voltas completas, terminando assim o sacrifício. Dois a dois, descem a os degraus e são saudados e abraçados à chegada. Já no interior do templo deitam-se, em decúbito ventral, para lhes serem retirados os ganchos «pela maior parte ensanguentados ».

Encontra-se documentado que em Bally e em Sirghão, aldeias da Província de Bicholim, também se realizava esta cerimónia durante o Zatrá . Tanto o Times India através do Dacca News, e o Hurkaru, Jornal de Calcutá mencionam cerimónias onde atos semelhantes aconteceriam: o Zatrá de Concão e o Charak Puja (Churruck Poojah) .

Em Goa, as cerimónias Os Enganchados foram proibidas pelo governador José Ferreira Pestana, no seu primeiro governo, em portaria de 6 de dezembro de 1844 (Boletim do Governo, nº 50 de 1844), onde se pode ler: «Não sendo possível que uma Nação civilizada permita que diante de seus olhos se cometam atrocidades, tais como suspender indivíduos por meio de ganchos, perfurando as carnes, (…) mandei chamar a minha presença o escrivão da aldeia de Cundaim de Pondá, a quem fiz saber a desaprovação do governo de Sua Majestade Fidelissima (…)». Esta decisão foi celebrada em diversas publicações como o Archivo de Pharmacia de 1865: «Esperamos que não tarde muito que outros usos e costumes religiosos hindus igualmente repugnantes sejam semelhantemente suprimidos» .

No entanto, durante o seu segundo governo, a 9 de fevereiro de 1866, os aldeões de Betqui, Goa, através de Minguel da Costa, solicitaram o restabelecimento desta cerimónia, uma vez que, segundo a sua carta, após a proibição da cerimónia de Os Enganchados várias pragas e calamidades teriam assolado a aldeia . De acordo com este relato, o governo de José Ferreira Pestana teria somente proibido a cerimónia realizada em Cundaim, tendo, noutras aldeias a mesma celebração sido impedida indevidamente pelas autoridades locais . «(…) esta proibição longe de ser proveitosa e benéfica à comunidade e aos mais habitantes da aldeia, tem sido pelo contrário, a fonte de toda a sorte de males e desventuras sucessivas para os habitantes da aldeia, a qual tem sido infligida seriamente por doenças epidémicas, mortandade imensa, absoluta falta de produção nos campos, e a subsequente miséria, e desgraças irremediáveis (…) toda a sorte de calamidades, resultante da secagem das lagoas das águas (…). Segundo a crença antiga, a população se persuade que deve atribuir todos esses males à falta da cerimónia dos enganchados (…)» . Nesta mesma carta o pedido é reforçado pelo facto de «semelhantes práticas existem em outros pontos da India» .

O governador José Ferreira Pestana respondeu, a 9 de fevereiro de 1866, rejeitando o pedido: «Quando o tradutor dos desejos dos suplicantes, Minguel da Costa, que este fez, me vier persuadir que da privação do Zatrá dos enganchados em Betqui e que aos suplicantes tem provindo os males, que referem, será possível considerar este requerimento.» (1866, p.50 – archivo de pharmacia) .

Minguel da Costa aparentemente não terá respondido ao governante mantendo-se, deste modo, proibida da cerimónia até à atualidade.

Marta Silva Pereira